Airport Development Group is your preferred partner for strategic infrastructure development & management in the Northern Territory.

Hotel Villas Honourees

ADG’s Hotel Villa Honouree project celebrates high achieving past and present Territorians who’ve made outstanding contributions to the preservation and celebration of Indigenous culture.

Please see the list of honourees below and click on their name to view their plaque and discover their story.

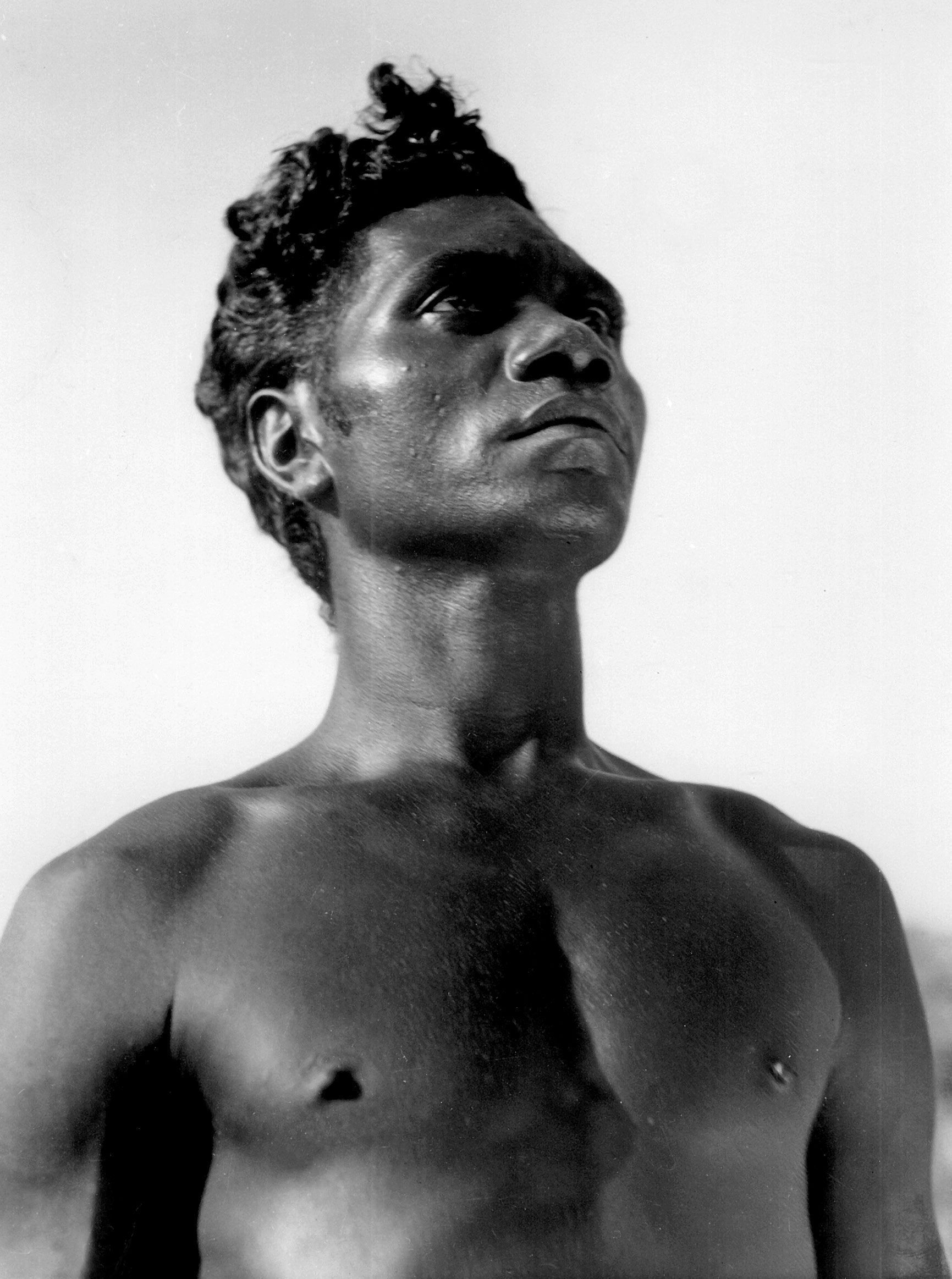

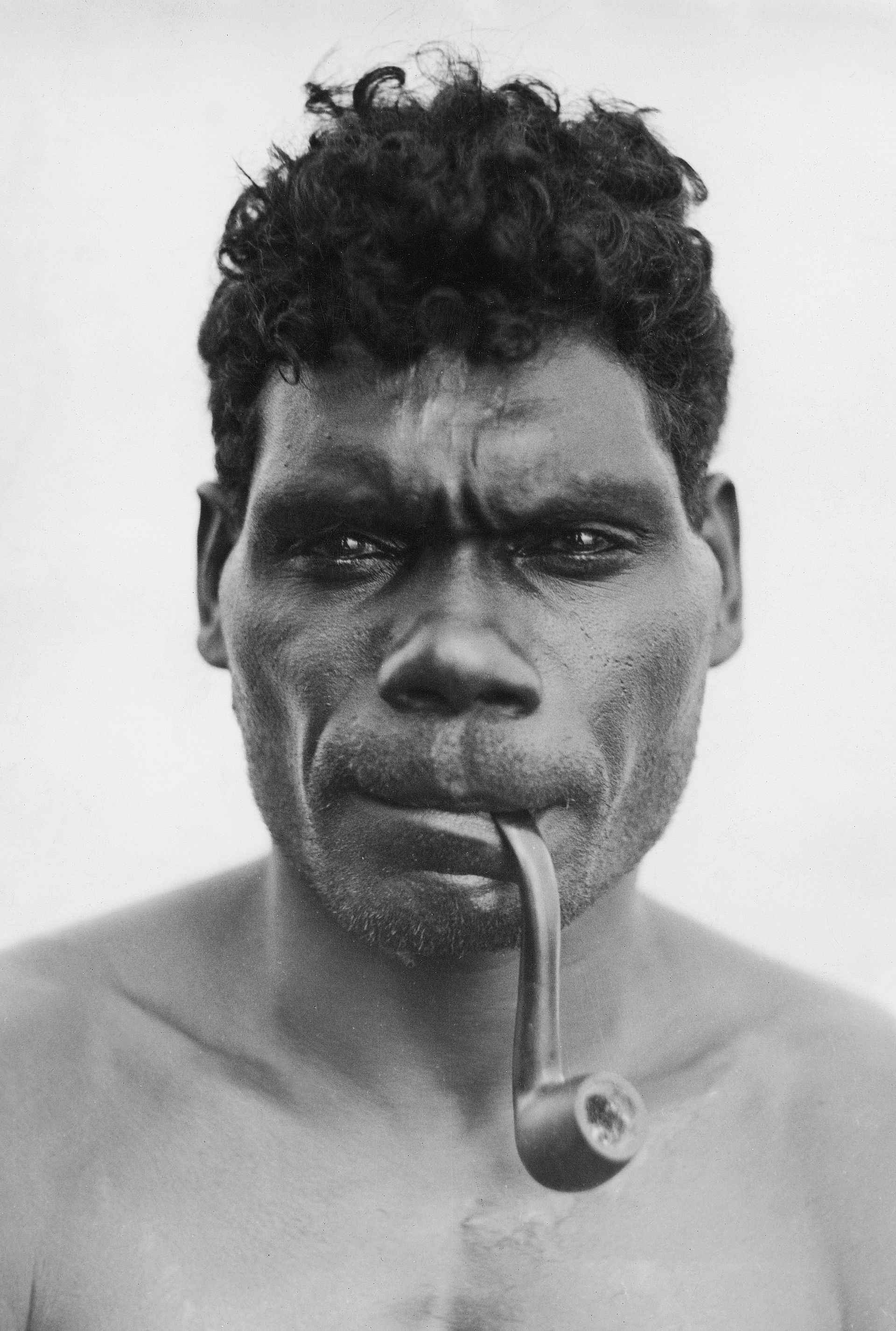

Billiamook in 1890, aged about 34 years. Photograph courtesy of the South Australian Museum Archives.

BILLIAMOOK

Billiamook was one of the first Larrakia to interact with white people, and was instrumental in establishing a respectful rapport between early settlers and the Larrakia people. The Larrakia people are the traditional owners of the Darwin region.

In 1869 young Billiamook was part of a group of Larrakia who met surveyor George Goyder’s party as they landed in the Top End. The party had been sent from Adelaide to map the future city of Palmerston (later renamed Darwin).

The Larrakia gave the surveyors a friendly welcome and the relationship between the two groups grew, with Billiamook playing a central role. He had quickly learnt English, making himself a valuable asset, acting as an interpreter and interface between European culture and his own Indigenous culture.

Through his work Billiamook earnt the respect of both the white settlers and traditional owners, becoming a well-known figure in the new community of Darwin.

The strength of this relationship in Darwin was in stark contrast to other parts of the country, where relations between Indigenous people and white settlers were marked by conflict and distrust. Billiamook was able to foster strong relations between the two parties.

Later in life Billiamook’s art was included in the 1888 Centennial International Exhibition in Melbourne, under the title ‘The Dawn of Art’. His artworks are recognised as contributing to the beginning of Aboriginal Art being recognised as ‘art’ and his legacy continues to

inspire Larrakia artists today

LINDA JACKSON (VALE)

In 2020 Linda Jackson (nee Vale) was honoured when NAIDOC named her the Territory’s Senior Female Elder of the Year. Linda was recognised for a lifetime of humanitarian commitment, a life full of service to others.

Linda was born in 1936, the child of Fanny, a Western Arrernte woman, and white pastoralist Snowy Pearce. In 1939 Linda was taken from her home at Lynda Vale station, in the Territory’s far south-west. She was put into government care at The Bungalow, in Alice Springs. In 1941 she was given to the care of Methodist missionaries and taken to Croker Island, off the Arnhem Land coast. By Christmas 1941 Linda was one of 95 children in care on the island, when war came to northern Australia.

Most civilians were quickly evacuated, but the children were left behind, with a few missionaries electing to remain and care for them. Finally, it was arranged that the children and their missionary carers would go to Methodist homes on the outskirts of Sydney

On 7 April 1942 the group travelled by lugger to the mainland, then they walked for 150 kilometres through Arnhem Land, then by rafts across crocodile infested rivers into what is now Kakadu, then by trucks and trains to Pine Creek, by military convoy to Alice Springs and

finally by train to Sydney. Five thousand kilometres across the continent, in six weeks. It was an Australian exodus without parallel. Linda and the other Croker Islanders remained in Sydney until the end of the war and returned home in 1946, aboard a naval vessel.

When she was about 16 years of age Linda went to Adelaide, where she completed her nursing training.

When the war ended, Linda and the other children were determined to return to the island home they recalled so fondly.

'At The Bungalow, I used to cry myself to sleep.', Linda remembered

For the next sixty years she worked in and around Adelaide and Perth hospitals, providing outreach to many thousands of people and, in particular, delivering mothercraft and family planning support to young Aboriginal women. Then, in 2013, she came back to Darwin to be with her surviving Croker Island friends. Linda remains grateful to the missionaries who protected and guided her through her early years and gave her essential life skills. Inspired by their example, Linda’s humanitarian commitment has sustained her in her desire to assist and serve others who may be in need. ‘I have had a fortunate life and I have always tried to give a hand to people who need help, I feel I was chosen to do that,’ Linda says

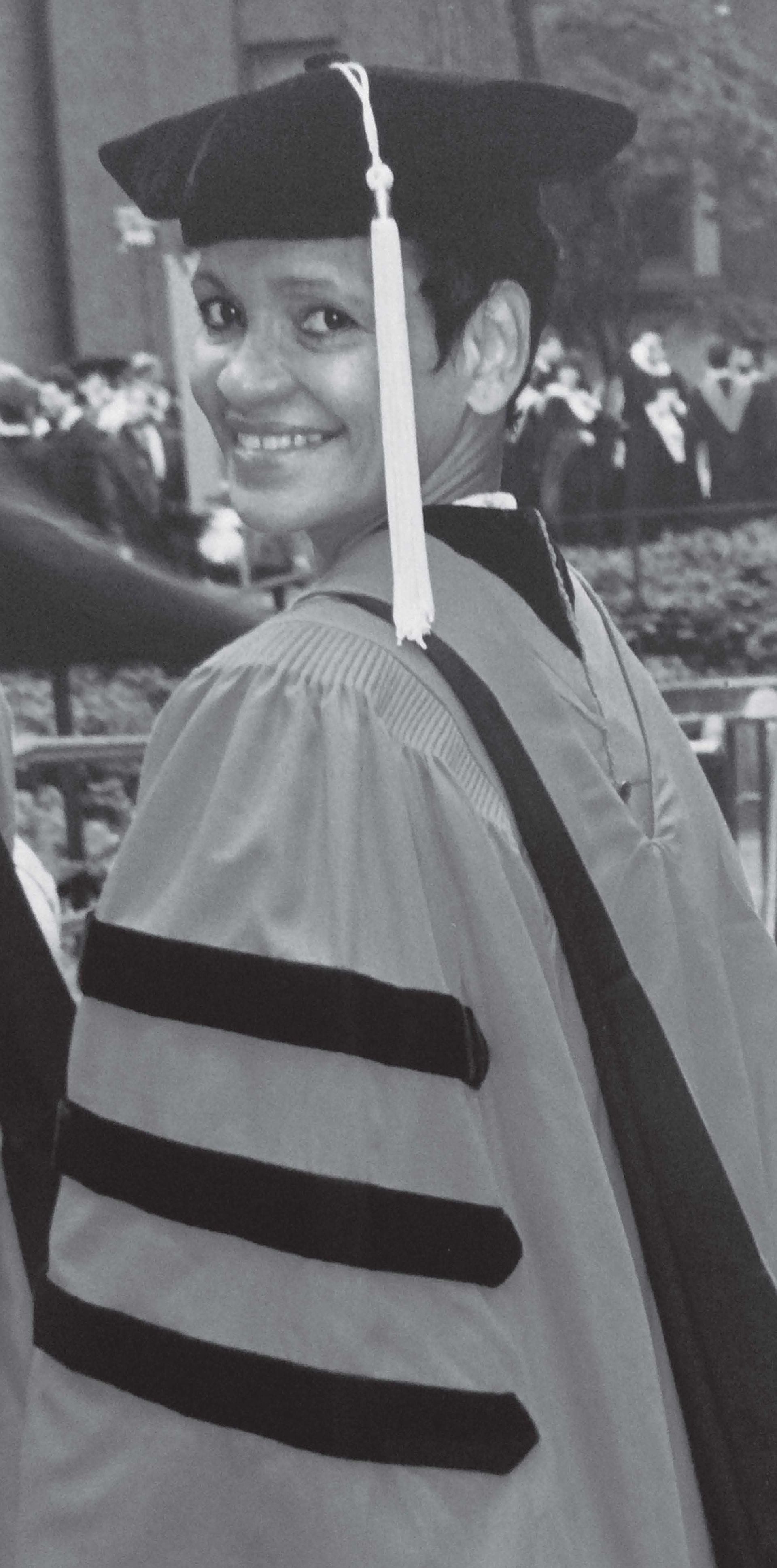

MaryAnn Bin-Sallik upon receipt of her Doctor of Education degree at Harvard University - just one of her many notable firsts.

EMERITUS PROFESSOR MARYANN BIN-SALLIK AO

MaryAnn Bin-Sallik’s eminent career has been distinguished by a catalogue of firsts, resulting in her being widely acclaimed as one of the highest achieving of all contemporary Australians.

In 1962 MaryAnn was the first Aboriginal person to graduate as a Registered Nurse through Darwin Hospital; in 1975 she was the first ever Aboriginal person to be employed full-time in Australian higher education; in 1989, she became the first Aboriginal Australian to receive a Doctorate from the world-leading Harvard University. MaryAnn didn’t stop there – Emeritus Professor; Pro-Vice-Chancellor; Officer of the Order of Australia; Special Recognition Medallist of the National Museum of Australia; NAIDOC’s National Female Elder for 2016 and NAIDOC Lifetime Achievement Award – these are just some of the awards and honours that together honour one thing – MaryAnn’s continuous and determined lifelong commitment to overcoming the effects of Aboriginal disadvantage.

This remarkable Australian was born in 1940, a Jaru woman of the Kimberley region. Her early childhood was in Broome but MaryAnn’s parents, Biddy and Sallim, thought there would be better chances in Darwin for MaryAnn and her adopted cousin, Albert. The family moved to Darwin in 1950.

Like so many other Darwin people in those early post war years, they lived in an ex-Army galvanised iron Sidney Williams hut. Sallim continued to work as a pearl diver and Biddy started a shop and drove a taxi so that the children could go to school in Adelaide.

‘Because of the commitment of my parents, I started with a big advantage, a good school education. When I was nursing I worked with a lot of Aboriginal people and I could see that their disadvantage could be overcome by education. That is why eventually I switched out of nursing and into Aboriginal education, working toward Australia’s first higher education and degree courses for indigenous people. That is what took me to Harvard and beyond.

‘I believe that the most beneficial changes for Aboriginal people have happened through education. I am pleased to be part of that, pleased to go on helping to change things for the better’ MaryAnn says.

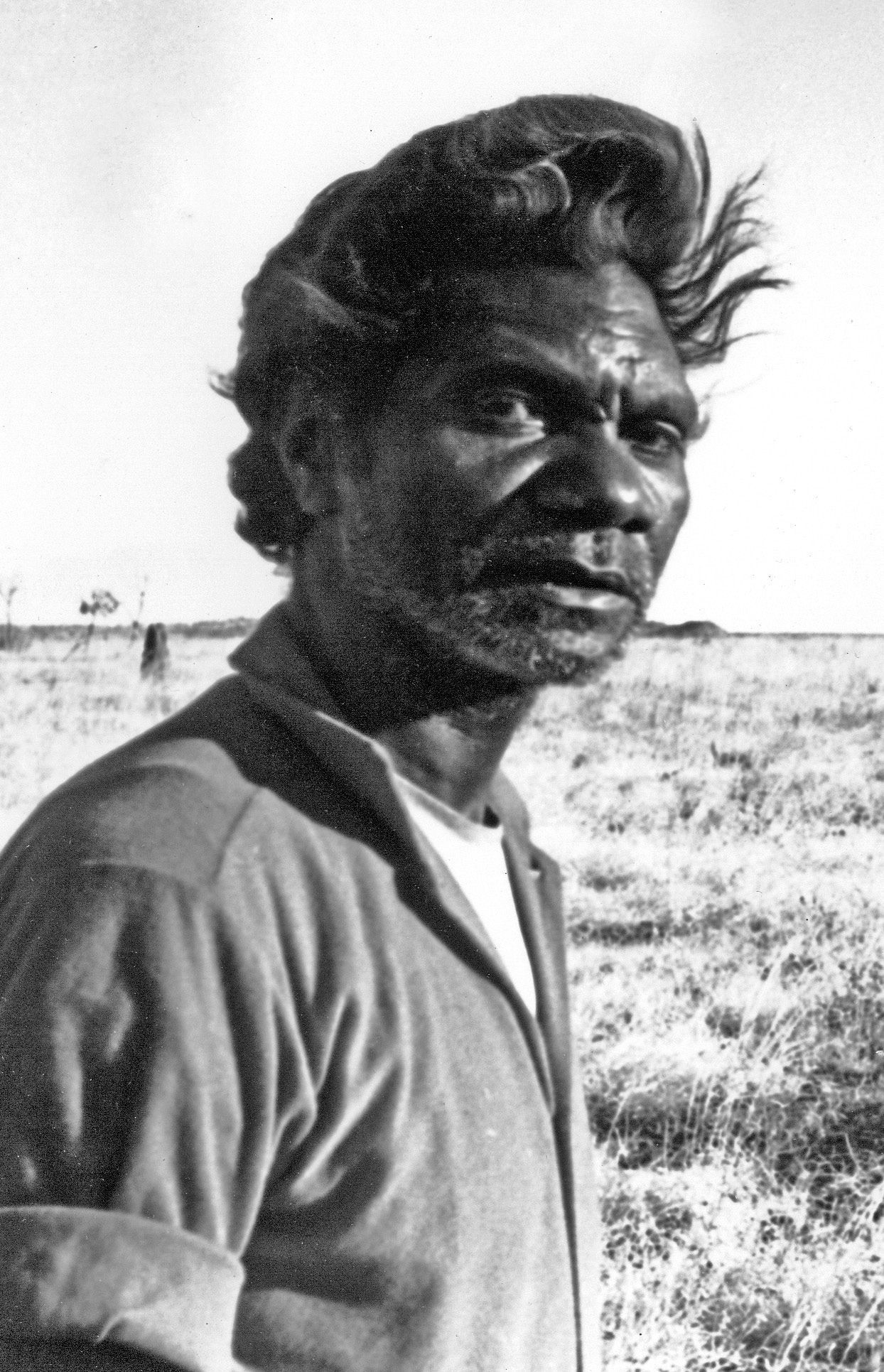

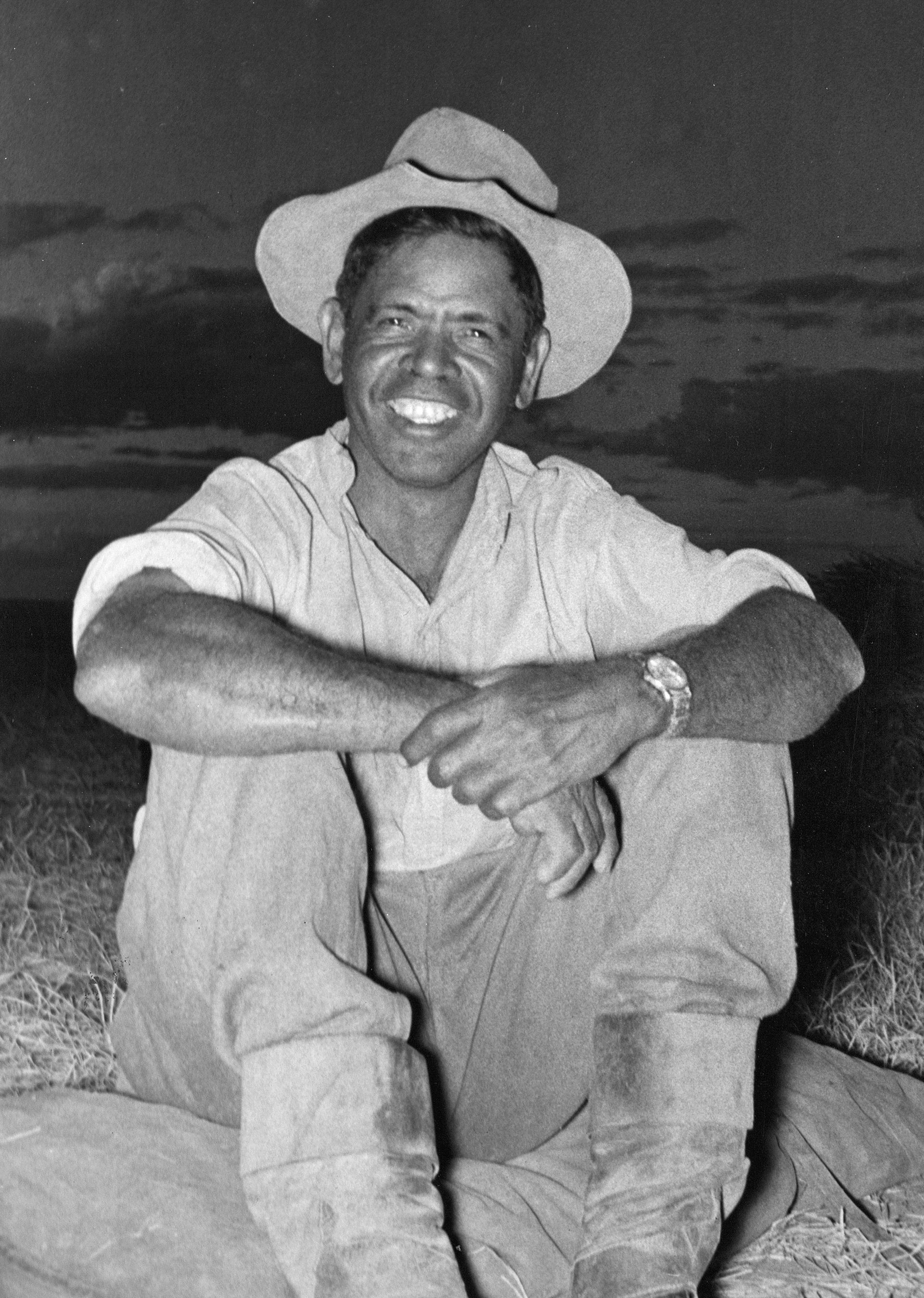

GEORGE MANFONG

He was known as ‘Gentleman George’ because everything he did he did well, without any fuss but always with quiet, dignified efficiency. By his skills, his example and his leadership he made good stockmen and he made good horses and good cattle.

He was born in about 1916, on Beetaloo station, near Newcastle Waters. His father, Fong Lai Man, was a Chinese gardener or perhaps a cook at the station; his mother was a local Aboriginal woman. When George was about ten years old he went to work in the stock camps at Beetaloo – a ‘camp’ comprised about a dozen stockmen, led by a headstockman. During each year’s dry season, about March to October, the camp moved across hundreds of square miles of country, gathering cattle and branding as they went. The cattle were drafted into mobs; the ‘fats’ (animals ready for the meatworks) were handed over to drovers who took the cattle on long walks to markets in Queensland or South Australia.

The camps were not places for men who wanted luxury but they were the universities of the bush. George Manfong graduated with honours.

In about 1940 George took a job with Vesteys, the giant English meat company that owned a string of stations that stretched from the Kimberley, across the Territory’s Top End and then into Queensland. Because it was such a big organisation, Vesteys could pick and choose its stockmen from among the best in the bush. George rose to very responsible positions with Vesteys and, had he been a white man, he would probably have become manager of Wave Hill, the plum job in the northern cattle country.

After 20 years George left Vesteys, to become a storekeeper at Newcastle Waters, then a drover and finally an itinerant saddler, travelling around stations repairing saddles and doing other leatherwork. Finally, in 1985, George took his family to Katherine, where he lived quietly until he died in 1994.

'Gentleman George' Manfong. Things are different in the outback now and Australia won't be making any more men like him.

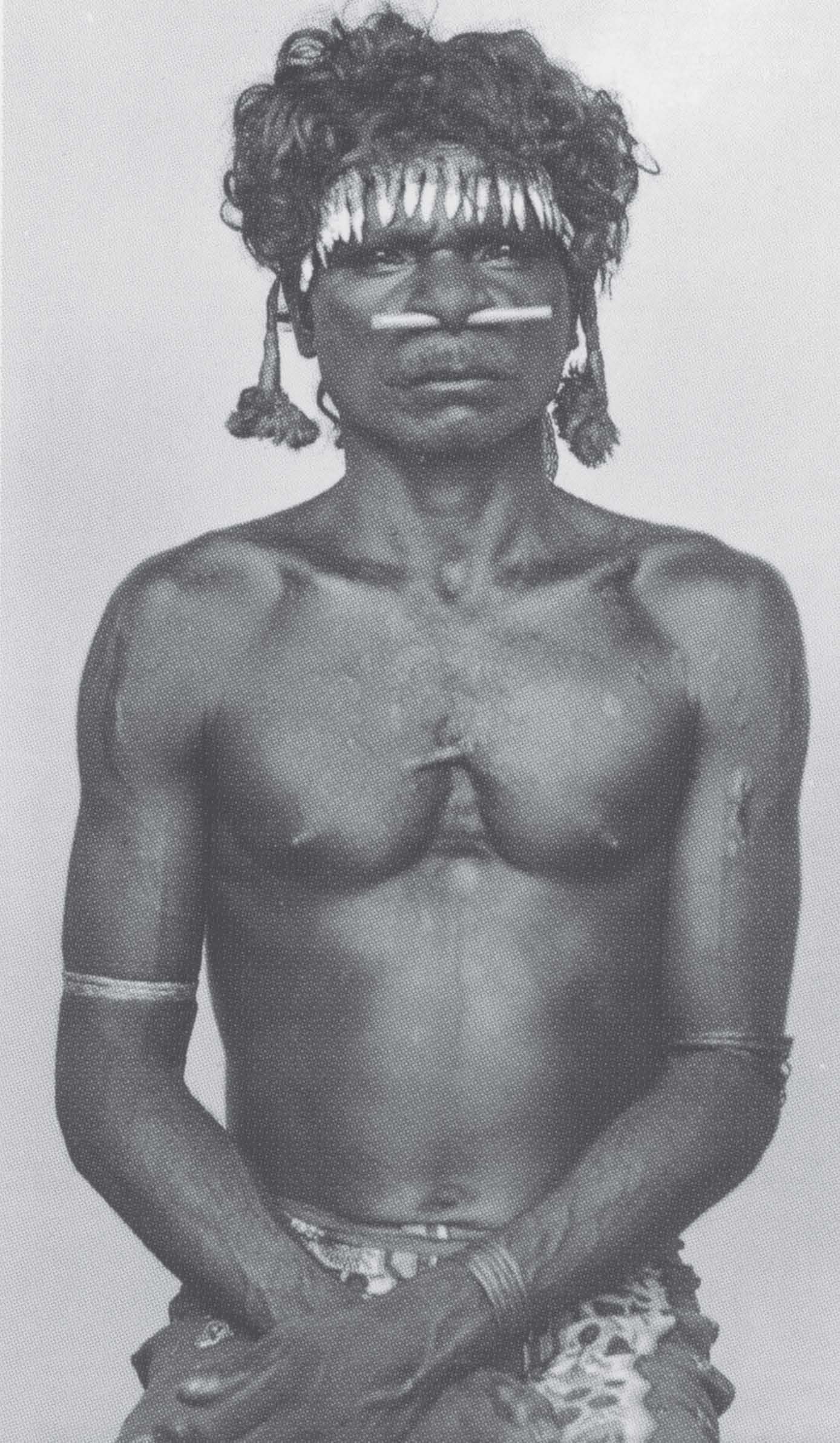

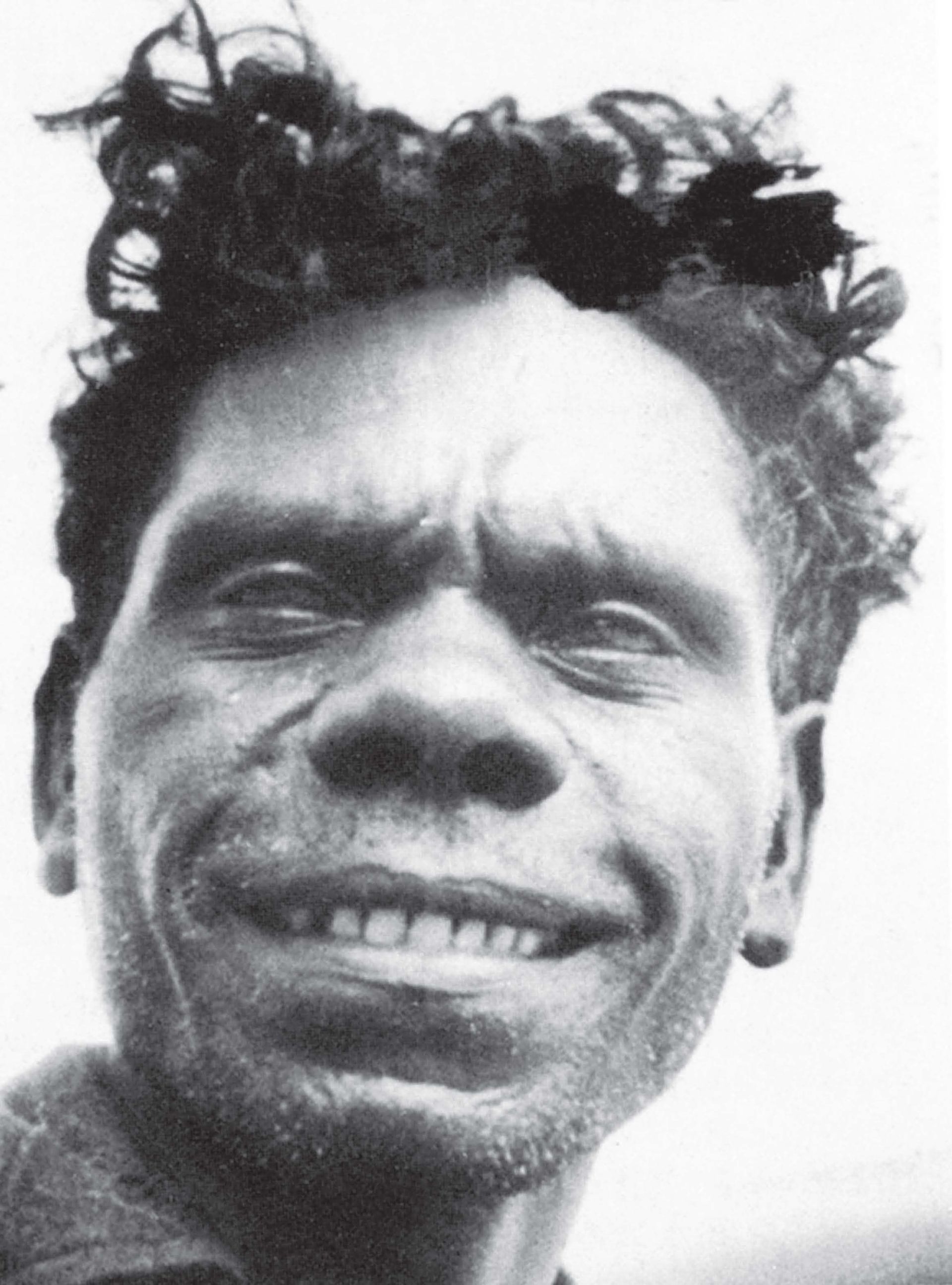

Matthias Ulungura - proudly remembered on the Tiwi islands

MATTHIAS ULUNGURA

‘STICK ‘EM UP, TWO HANDS, RIGHT UP’

During the last few years of the 1930s, when war with Japan seemed ever more likely, there was much anxiety about the loyalties of the Aboriginal people of north Australia. In the event of war, might they side with the enemy?

Tiwi man Matthias Ulungura put all the anxiety to rest. On 20 or 21 February 1942 he demonstrated remarkable coolness, courage and efficiency when he captured the Japanese pilot Hajime Toyoshima, the first man ever to be taken prisoner of war on Australian soil.

Toyoshima had flown a Zero fighter during the first air raid on Darwin, on 19 February 1942. As the raid ended the Zero was hit by small arms fire. Toyoshima crash landed the plane on Melville Island. The plane was badly damaged, but Toyoshima was only slightly injured.

Toyoshima began wandering in the bush when he encountered a group of Tiwi women. Matthias saw him and watched, unseen, as the pilot threw papers onto the women’s campfire.

Then Matthias stalked the airman from behind. He grabbed his right arm to stop him shooting, took the revolver from his pocket steeped back and said “Stick ‘em up, two hands right up, straight up.” Toyoshima knew better than to resist! Matthias was joined by other Tiwi warriors and together they took Toyoshima across to Bathurst Island and handed him to military authorities.

Matthias built on his unique war record during the next few years when he led patrols looking for shot-down Allied airmen and possible Japanese invaders. Matthias died in 1980. Matthias’ courage has been widely acknowledged in literature and by memorials. A memorial cairn was created by the Northern Territory Government in 1985 and a life-sized bronze statue was installed on Bathurst Island in 2016.

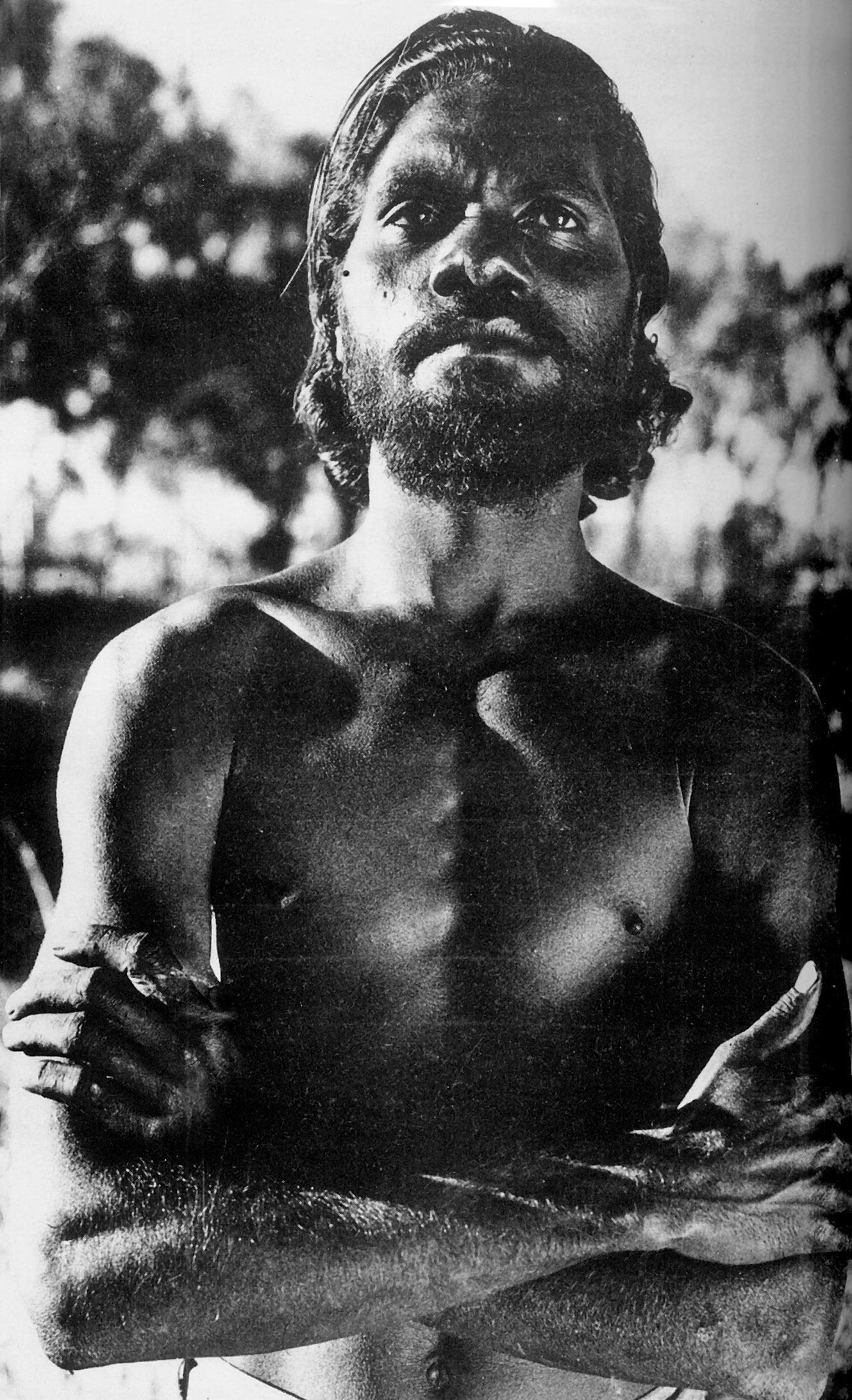

MATHIAS NEMARLUK

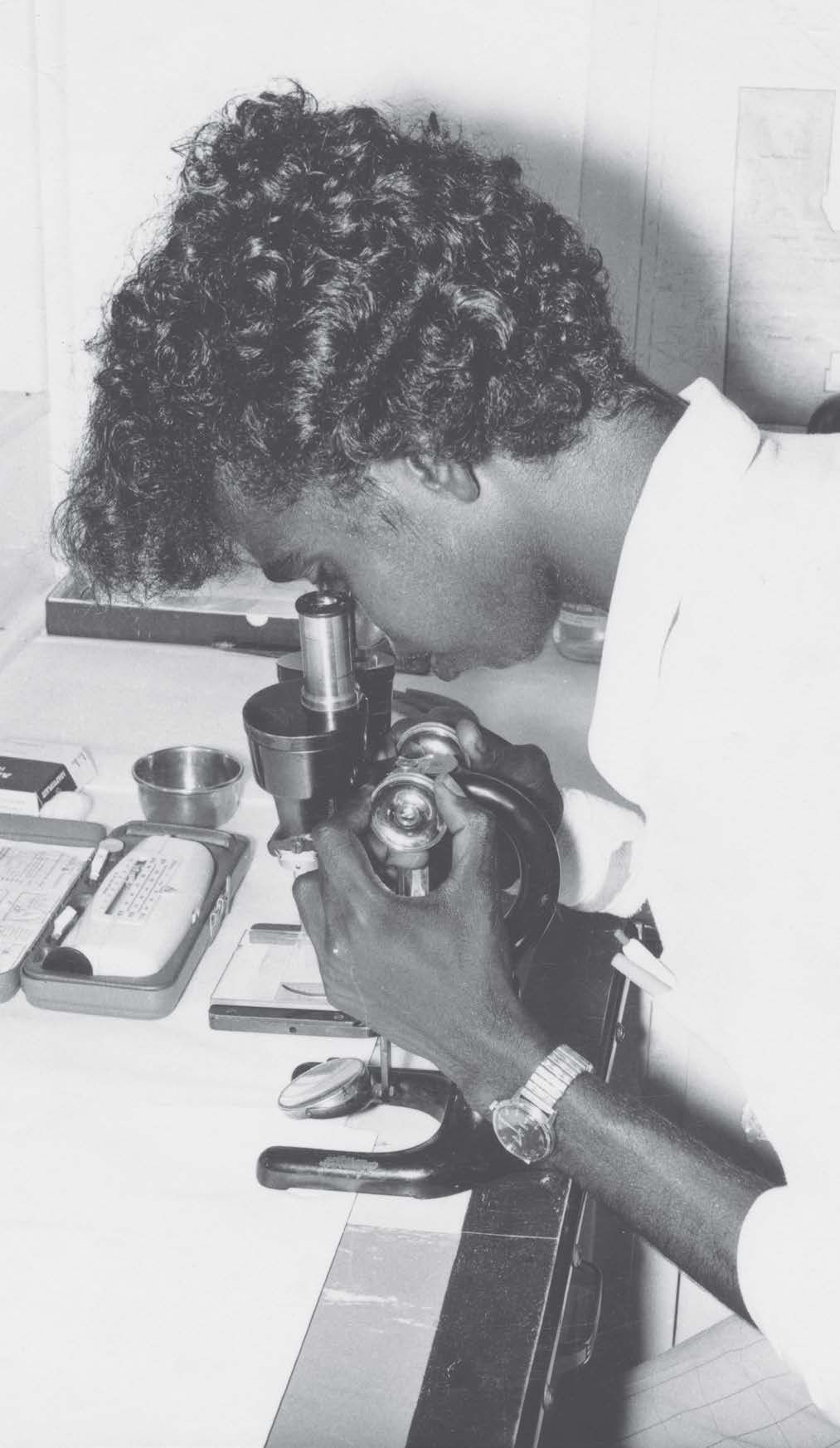

Tjeyenga Mathias Nemarluk is an Aboriginal man of rare, perhaps unique, distinction. He played a leading part in pioneering new surgical techniques to restore hand and foot function in leprosy sufferers. He was also at the forefront of implementing new policies for the treatment of leprosy in the community. He made many lives better.

From the 1870s, leprosy began to spread among the Aboriginal people of north Australia. For years there was no prospect of a cure, until Mathias and others brought hope.

Mathias was born at Port Keats (now Wadeye) in 1955. As a young man he learned a lot about leprosy when both of his parents contracted the disease. The family sought treatment as inpatients at the East Arm leprosarium, on the outskirts of Darwin. Mathias went with his family and he was given a choice – go back to school or stay and start formal nursing training. Mathias chose nursing.

The outstanding leprosy specialist, Dr John Hargrave, wanted to improve the lives of Aboriginal people by eliminating leprosy from the Territory’s Top End. He saw something special in young Mathias. First, he gave Mathias responsibility for preparing and sterilising surgical instruments. Then he got Mathias to assist with surgical operations designed to give patients back the use of their fingers and toes, which had been disabled as leprosy slowly destroyed the patient’s nervous system.

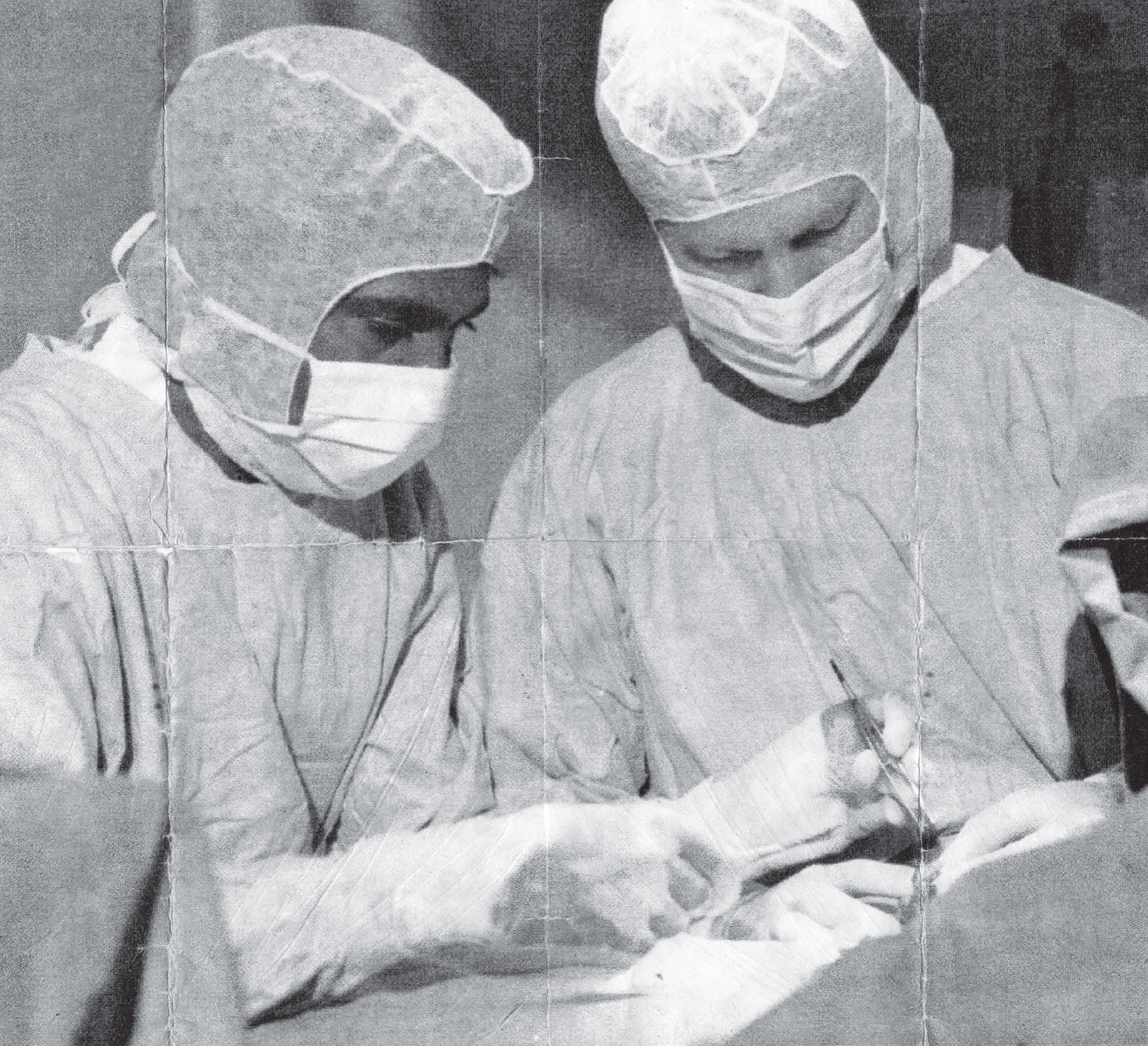

Mathias at work at East Arm.

Mathias and Dr John Hargrave at work in the East Arm operating theatre.

The surgical procedures involved taking a little used nerve from the leg of a patient and transplanting it for connection to the damaged hand or foot. Mathias showed amazing dexterity at this work.

Later, Mathias was a pioneer remote area Aboriginal Health Worker whose task it was to treat leprosy in the community. He gave sufferers the confidence to embrace new humane and systematic treatments that offered an excellent chance of a cure. Gradually, leprosy was brought under control and the fear of it gave way to hope.

Matthias Ulungura - proudly remembered on the Tiwi islands

ROBERT SHEPHERD

Darwin people assembled at the Town Hall on 15 December 1917 to farewell 23 local men who had enlisted to serve in the Australian Imperial Force during World War One. One of the volunteers was Larrakia man Robert Shepherd. His father Billy Shepherd was a highly regarded employee at Government House. His mother, Ruby, died while giving birth to him.

Robert was one of over 1000 Indigenous Australians who enlisted to serve in the First World War. At the time most Indigenous Australians could not vote and none were counted in the census. Robert went to an army camp outside Sydney for introductory training before being deployed to the Middle East. He was selected to join a Signals Training school, then joined the 11th Light Horse Regiment. Robert took part in the battle of Samakh on 25 September 1918. This battle resulted in a notable victory.

Robert then succumbed to the ‘Spanish flu’ that was sweeping through the armed forces. He was hospitalised and by the time he could re-join his regiment, the war had ended. He returned to Australia in August 1919 and came back to Darwin with a military detachment that was sent north to maintain order during industrial disturbances.

After his discharge he worked as a labourer and was treated with respect and admiration for his war service. However, he found it difficult to settle down, as was sadly the case with so many veterans of World War One and he gradually surrenderedto the solace of alcohol.

In 1937, his body was discovered at the bottom of the Emery Point cliffs. Darwin people gave him a soldier’s funeral and returned servicemen carried his coffin. His wife Maggie and children Nellie, Robert, Patsy and Pauline survived him. Today, their descendants are prominent members of the Darwin community.

BROTHER JOHN PYE

Over on the Tiwi islands they called him ‘Punderlime’, which means strength and endurance. Brother John Pye MSC had those qualities in abundance. For sixty years he worked among Aboriginal people on the Tiwi Islands, at Port Keats and at Daly River. Wherever he went, he made lives better.

Born in southern New South Wales in 1906, John Pye trained at first to be a diesel engineer. However, his imagination had always been fired by stories of missionaries and he chose to join the Sacred Heart (MSC) missionary order. For ten years he taught at a school in Queensland, then he was called to work with the MSC in the Northern Territory.

In late 1940 Brother John sailed for Darwin on a troop ship. In February 1941 he visited the Catholic mission at Bathurst Island. ‘I was amazed,’ he said. ‘Tradition and customary law were still very strong. We missionaries are often blamed for destroying Aboriginal traditions. We didn’t change or destroy tradition, we built on it, we helped it to evolve.’

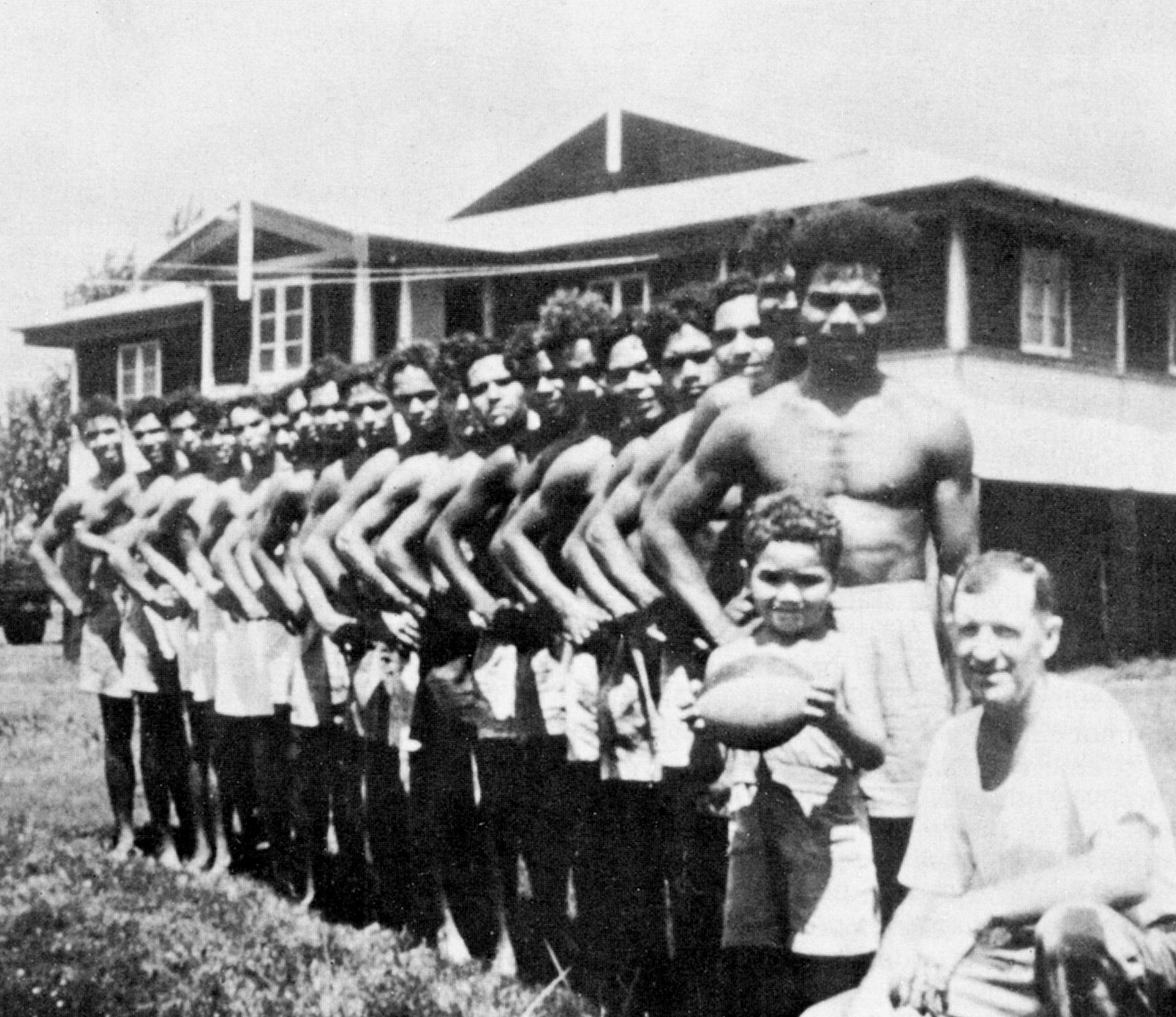

Brother John’s greatest contribution to that evolution was to introduce Australian Rules football, first to the Tiwi Islands, where he served after three years at Port Keats. ‘The Tiwi played a simple game with a ball, no rules. I put up some goalposts on a disused military airstrip and I taught them how to play Australian Rules. Before long there were organised teams playing a competition, the mission versus Garden Point. The game made big difference to life at the mission because the people worked off all their aggression on the football field.’

Tiwi footballers are now renowned and sought after across Australia.

Brother John Pye, with one of his early Tiwi football teams. Brother John kicked a splendid goal when he brought Australian Rules to Top End Aboriginal communities in the 1940s. Brother John died in 2009.

Geoffrey Mungatopi knew the north coast like the palm of his hand.

GEOFFREY MUNGATOPI

By the mid-1930s, Australia was nervous about the likelihood of war and the activities of hundreds of Japanese pearling boats that were operating in waters off the north coast. Local pearlers were jealous; defence authorities were anxious; others were concerned about Japanese landfalls for the purposes of taking fresh water and Aboriginal women.

Public opinion demanded that ‘something must be done’. The government response was to base a patrol vessel, the Larrakia, at Darwin. Its tasks were to patrol the northern coastlines, to keep the Japanese vessels well offshore, and to respond to any disasters that might befall flying boats as they flew between Darwin and Singapore.

The Larrakia arrived in Darwin in May 1936, fully manned and equipped – except that its crew had no knowledge of northern waters, nor any useful charts. Captain Haultain cast about for a pilot, someone who knew the coasts and their people. Bathurst Island missionary and captain of the mission boat, Brother Smith, told Haultain ‘I have a man in my crew who knows the islands like the palm of his hand. If I can persuade him to join your ship your piloting worries will be over. He is a first class sailor, willing reliable and truthful.’

Geoffrey Mungatopi was persuaded to join the Larrakia and before long Haultain called him ‘the doyen of the pilots. At the wheel I followed his every signal. He acts as pilot and general deck hand. Geoffrey is an outstanding type of Australian Aborigine, invaluable to the patrol service since its inauguration.’ Haultain had special reason to be grateful – once, on Bathurst Island, Geoffrey rescued the captain from a crocodile attack. The two men spent all night together, up a tree, until the crocodile finally gave up.

Geoffrey served on the Larrakia until 1939, when the vessel was directed to other duties. Geoffrey returned to Snake Bay, on Melville Island, where he became a respected artist, ‘ceremony man’ and keeper of Tiwi tradition. He died in about 1975, aged about 65 years.

MICK MARKHAM

Mick Markham’s life was full of skill and achievement, full of humour and goodwill. He started his working life as a stockman at age 12, then became a soldier, a senior Jawoyn leader, long-time chairman of the Gunlom Aboriginal Land Trust and the Kakadu Board of Management. He was a teller of wonderful stories and a bush entertainer who loved playing the spoons as he sang.

Above all, he was a role model, a mentor and a man with a total commitment to looking after people and country. Mick was born in Pine Creek in 1947, the son of Jawoyn woman Susan Kelly and an Irish cattleman, Bob Markham. His early childhood was in Darwin. Mick said ‘I had a bit of schooling, but not much’. His education quickened when he started working for pastoralist Bill Bright at Stapleton station. He said ‘I learned to ride rough horses, muster wild cattle, sleep on the ground and live on damper and beef. Then I went to work for the Townsends, newly arrived American cattlemen. They fed me, they taught me and they paid me – I thought the pay was a bonus, I wasn’t used to it!’

Mick loved the life and would have lived it forever but, in 1968, he was called up for National Service and active duty in Vietnam with the 9th. Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment.

He served as a machine gunner in a support section with the tasks of protecting senior officers, backing up ambushes, securing communications and guiding food drops. ‘My motto is “Respect the dead and fight like hell for the living” and that is what I have tried

to do,’ Mick said. He lived up to that, he worked tirelessly for the welfare of veterans of Vietnam and later conflicts. He has also raised thousands of dollars to benefit Vietnamese orphans.

In later years Mick worked to protect places of special significance to Aboriginal people. ‘There are places that are full of spirituality, places that give Aboriginal people a sense of belonging. We have got to look after those places, otherwise you have got nothing in the end.’

Mick died in September 2021. To the end, he never lost his passion for caring for family and country.

No-one was ever bored while Mick was around.

Aunt Nellie, holding Miriam-Rose, about 1954.

Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr Baumann - a life full of honour and honours.

MIRIAM-ROSE UNGUNMERR BAUMANN

She has been everywhere – to Antarctica as an Indigenous Person and Artist in the 1994 International Year of Indigenous Peoples, to London in 2022 as a distinguished guest at the funeral of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and to many places in between.

Dr Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr Baumann AM was born in the bush near Daly River, in 1950. The Ngengiwumirri language is her native tongue but she is fluent in four other local languages as well as English.

As a child, Miriam-Rose lived with an aunt and uncle and attended several government schools. When she was 14 years old she returned to Daly River and went to the mission school there. In 1965 she was baptised into the Catholic faith.

In 1968 Miriam-Rose began studies toward a school-teaching career and, in 1975, she became the Territory’s first fully qualified Aboriginal teacher. Along the way, Miriam-Rose became keenly interested in painting, making her strongly committed to encouraging the development of art as part of every child’s education.

She realised that non-Aboriginal children were keen to hear more about Aboriginal people and their ways of life. She also saw the need for Aboriginal people to have their own qualified teachers and to manage their own schools. Miriam-Rose encouraged Aboriginal women to study to became teachers – with the eventual result that St. Francis Xavier school at Daly River came to be entirely staffed and managed by Aboriginal people. In 1993 she was appointed principal of the school.

Parallel to all this, Miriam-Rose established the acclaimed Merrepin Arts Centre, with the support of Daly River women. The main objective was to create a gathering place that would strengthen community identity and sense of place, as well as fostering adult education through artistic endeavour.

Miriam-Rose has significantly contributed to new appreciation of the interfaces between spirituality, art and education. She has been much honoured for these and many other contributions to education and to the general community.

NEIGHBOUR

In December 1912, that was the newspaper headline everywhere between London and Melbourne. The stories told of the award of the Albert Medal, then the highest British Empire award for civilian bravery on land. The recipient was a Roper River Aboriginal man named Ayaiga, better known to history as Neighbour.

On 1 February 1911 Mounted Constable William Johns, stationed at the Roper River police station, had four Aboriginal prisoners, including Neighbour, in his custody. He had arrested the men after complaints that they had raided a fencer’s camp and had been killing cattle. Johns put neck chains on the prisoners and set off for the police station with the men.

When the party came to the Wilton River it was in high flood. Johns directed the prisoners to swim across the river in front of him while he followed on horseback. About half way across John’s horse stumbled and the horse kicked the policeman on the head. Johns was knocked unconscious. The prisoners reached the riverbank and saw what had happened. ‘Without a moment’s hesitation, Neighbour plunged in to the constable’s rescue and, after a great struggle, succeeded in dragging him to safety on the river bank,’ reported the Northern Territory Times newspaper.

Eventually, Johns re-assembled his party and proceeded with the journey toward courtroom justice. When the case against Neighbour was presented, Johns offered no evidence and Neighbour was discharged without conviction.

Many people felt that this outcome was insufficient recognition of Neighbour’s bravery. Representations were made as far afield as Buckingham Palace and eventually the King directed that Neighbour should be awarded the Albert Medal. The medal was presented to Neighbour in December 1912, at a ceremony in Darwin’s Government House.

Neighbour lived in the Roper River district until his death in June, 1954. He was at times employed as a police tracker; at other times as a stockman.

It was acknowledged that Neighbour was the first Aboriginal person to be honoured in this way and that his action set an example for all Australians.

'Love and courage can create a strong community that will be able to handle the challenges of the present day' Sister Anne says.

SISTER ANNE GARDINER

In 1952 a young woman met in Sydney with Francis Xavier Gsell, retired Bishop of the Northern Territory and the man who had started Catholic missionary endeavour on Bathurst Island in 1911. The young woman was Anne Gardiner, who had completed her novitiate training in the congregation of the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart and was studying at the Order’s head house at Kensington in Sydney.

She said to the Bishop ‘My Lord, I have been selected to go to work at the mission on Bathurst Island. What should I do?’ Gsell thought for what seemed like a long time and then said simply “Love them”. And that is what I have been trying to do ever since, love them, the people of the island’ Sister Anne said.

Sister Anne has lived a life of compassion and service. For 14 years after she arrived on Bathurst Island in 1953 she lived in a dormitory with Tiwi girls, ‘the happiest years of my life’ she says. She began teaching, underneath the island’s church – starting with about 80 boys and girls in one big class. Slates and chalk were her only aids.

She spent quite a few years teaching elsewhere. But she was always overjoyed to come back to Bathurst Island to be with the Tiwi again. ‘The Tiwi have literally made my life, they have given me so much loyalty and support. They have taught me so much about accepting and forgiving. The Tiwi women have inspired me with their example of womanly dignity,’ Sister Anne says.

Her special task has been to help document and preserve Tiwi language, culture and heritage. In the early 2000s she established the Patakijiyali museum at Wurrimiyanga on Bathurst Island. The museum holds a splendid collection of materials that evidence the Tiwi partnership with the Catholic mission as well as the proud roles of the Tiwi in World War Two and sport.

TUDAWALI

Robert Tudawali challenged the white world when he played the traditional Aboriginal man, Marbuck, in the 1955 film Jedda. The film had as its central theme the tensions arising out of the transition of Aboriginal people from the traditional world to the modern. Tudawali was a sensation and the film was a great success. It was the first Australian feature film to be produced in full colour and it was the first to put Aboriginal people into the leading roles.

Tudawali, a Tiwi man, was born on Melville Island in about 1929. In the late 1930s he was taken to Darwin by his parents. He soon came to be known in Darwin as ‘Bobby Wilson’ – a name derived from his parents’ employers.

Tudawali received a rudimentary formal education at the Native Affairs Branch school at Kahlin Compound. Rudimentary or not, he acquired a rich English vocabulary and spoke in beautifully modulated tones. He later became an excellent footballer – one opponent, Ted Egan, recalled trying, unsuccessfully, to get past him. As Ted picked himself up after a hard tackle, Tudawali said ‘Well played, old chap!’

Late in 1941 Tudawali became a medical orderly at an RAAF medical aid post; then, after the first air raids on Darwin, he was moved to Mataranka to work in a mechanical workshop. Late in the war he was moved back to Darwin to work as a steward at Larrakeyah military barracks – proof of his style and self-assurance.

After Jedda, Tudawali appeared in the television production Whiplash, and in several films. But his was a troubled life – his first marriage collapsed and he was afflicted by both tuberculosis and alcoholism. He was in and out of both hospital and jail. However, Tudawali’s life was given new purpose in 1966 when he became Vice-President of the NT Council for Aboriginal Rights. He publicly advocated equality and self-determination for Aboriginal people and played a significant role in supporting the people who had ‘walked off’ Wave Hill station.

In July 1967 he was severely burned in a fire at Bagot settlement, in Darwin. He died of the burns and of tuberculosis on 26 July 1967.